Diet Strategies & Nutrition: Low Carb, Intermittent Fasting, Liquid Diets, IIFYM, Calorie Restriction. What The Hell Do I Do?!

Let’s go back to the early nineties. A simpler time, when a person actually made eye contact when you spoke and your girlfriend needed more than your Facebook password to find out if you were cheating on her. Back then the internet was dial up, remember whenever you picked up the phone it sounded like it was dying in agony. It was nowhere near as widespread. Some homes didn’t even have a computer. Imagine! Back then people didn’t know much about diet and exercise. In fact, personal trainers used to be comparatively sparse and they used to RAKE in the money! And then the apocalypse happened….

BOOM! The internet hit! And hit hard! Broadband made internet faster and eventually dial up wasn’t required. Not too long later social networks hit (remember Bebo and MySpace?). Information could now travel faster than ever and was waaaaaaay more accessible. Now all of a sudden everyone was an expert on diet and exercise and, we, as trainers, lost our fucking minds! We turned into internet experts ourselves! Chanting the wonders of the Atkins (low-carbohydrate) diet, low fat diets, juice diets and, more recently, Intermittent Fasting. Finding out what a bench press or a low carb diet plan was meant googling it. And, yeah, in case you didn’t guess it, the going rate for a personal trainer went down faster than an obese skydiver with an anchor for a parachute. But even worse, we’ve now got certification courses being run by trainers who couldn’t coach a blind man across the road, imparting their wonderful biases on students (I’m looking at you Poliquin-ites!). We’ve become the equivalent of religious nuts (which will actually be the subject of my next post) and all of a sudden, losing weight wasn’t just as simple as eating a little less (calorie restriction) and exercising a little more. Meanwhile, the media machine jumped on the health bandwagon, condemning Fat in the early noughties, Carbohydrates over the last 3-5 years and, only the year before last, ran a story about the dangers of protein (Knapton, 2014). I really hope there’s a special place reserved in hell for those morons. They actually compared a high protein diet to SMOKING!!

As Charles Poliquin put it in one of his posts, “so that’s carbs, fats and protein that’s bad for you. What’s left? Water?”. Pretty much. But then again don’t they lace that stuff with Flouride? Guess that’s out too.

As sarcastic as Poliquin was being, he did allude to a valuable question in his post. What is the best diet protocol? Is there a “best” protocol? Is there at least one diet that’s “better” than another for a certain type of goal (i.e. weight loss,weight/Muscle gain, improved Endurance/Strength performance)?

See, there’s nothing new in the spread of misinformation (or disinformation) in health and fitness, with Men’s Health and other fitness magazines preceeding the internet by quite a bit. But its way more widespread now, and the trick has become, not finding the information, but filtering it. What sources are good (peer reviewed articles from Google Scholar and Pubmed) and what sources are bad (most fitness magazines and general media). But the problem is the answer from the good sources are not always so flashy, definitive, or even easy to understand, with all those numbers and symbols. Took me long enough to find out what a p value is and I’m a freaking sport scientist!

So, what IS the best protocol? What does the “good” sources say? Let’s have a look.

Low Carb/Keto/Atkins Dieting

Okay, so let’s start with one of the oldest diet fads. The old low carb crazy, which actually seems to be making a pretty impressive comeback at the moment (Cox, 2016). Let’s clarify. There are two main types of a low Carbohydrates diet:

- Reduced Carbohydrate or simply a “low” Carbohydrate diet, which basically is when the person reduces his/her Intake of Carbohydrate (usually to under 300 grams up to about 100 to 200 grams being around normal, but there’s no hardcore number).

- A Ketogenic or “Atkins” (named after a doctor who popularised it) Diet, which is the one that is hailed as the one with all the benefits in research, as it ha the most definitive criteria. Carbohydrates are kept under 25g per day, or, in some cases, under 50g per day. The idea behind this being that when Carbohydrates are kept this low, the liver will produce something called Ketones, which basically help spare glucose in the blood and use Fat as the primary source of fuel for the body. After about two weeks of usually feeling awful, more on this in a bit, your body becomes “keto-adapted” and you use fat as your primary energy source.

So, does it work? Well, “work” is a relative term. Work for what? Improving body Muscle/fat Ratio? Strength gain? Endurance gain? Weight loss?

Okay, so does it work better than a regular diet (around 70% carbs, 15% fat, 15% protein) for improving Endurance? And, just like that it’s time to quote a study that has caused more arguments than that poor tree that fell in the forrest when no one was listening.

Phinney et al, 1983:

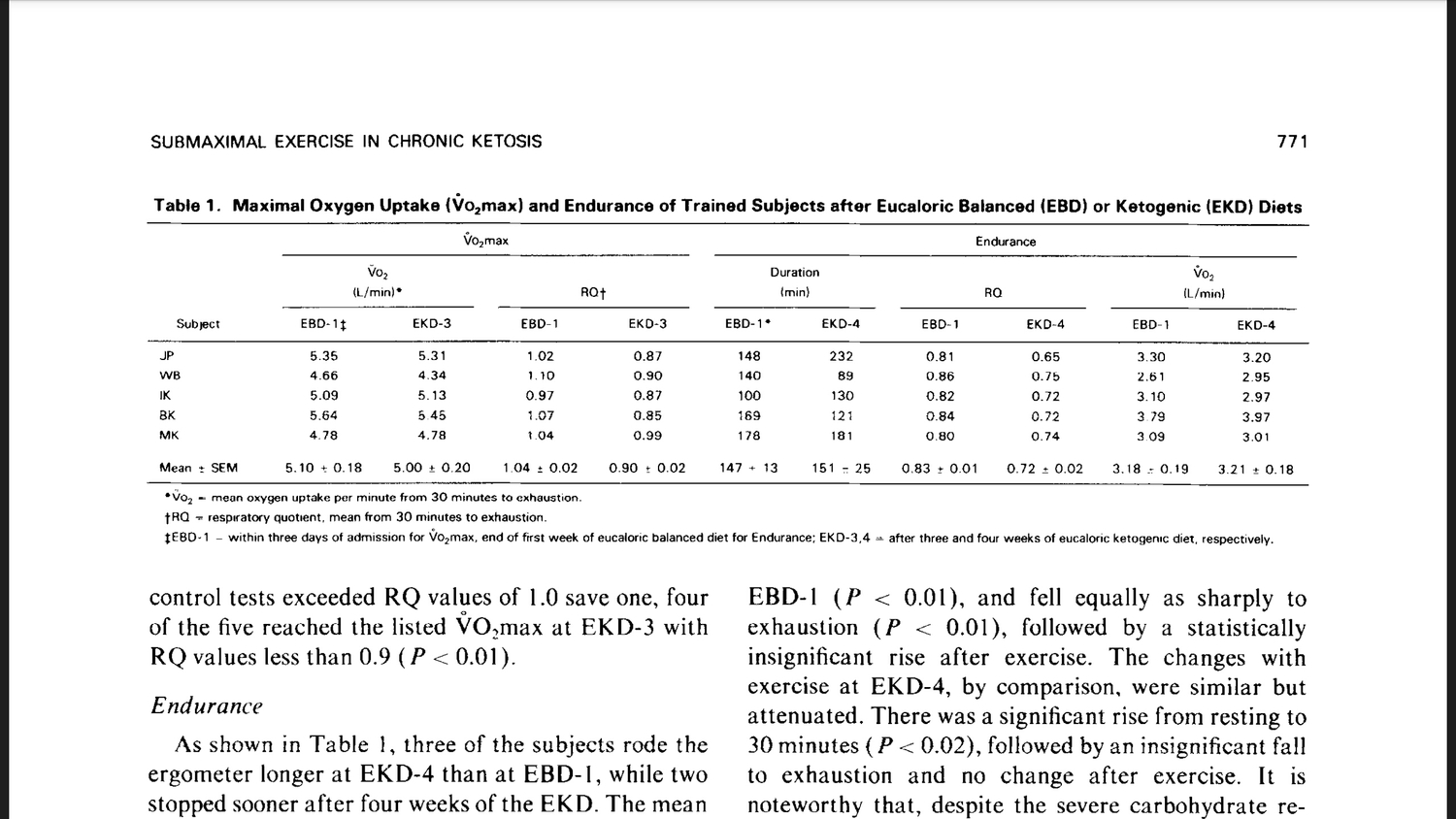

Phinney and his boys basically took a couple of Endurance cyclists and put them on a low carb diet, allowed them two weeks to adapt, and tested them. They found the average time to exhaustion (endurance) increased by four minutes for the Keto group. Success, right?

Nope. And this is why studies can be a problem in interpreting if only the abstract is read or if the author isn’t fully disclosing the details in it.

In fairness, Phinney has to be given credit, he got a bunch of trained cyclists to follow a diet that’s very difficult to follow for two weeks, and he did disclose each individual’s results, unlike Lambert and colleague’s study which just gave the averages. And herein lies the issue. Below you can see the table of the results. And what do they reveal? Two cyclists got better, one of them getting really good results, two got WORSE and one stayed the same. Because one of the improved group got such good results, it inflated the average of the group. Lambert and colleague’s did a similar study and found a significant improvement in the Keto group but DIDN’T report individual results, which makes me skeptical. On, and in both cases there was no control group.

Wait, what do you mean “got worse?!” How could decreasing Carbohydrates make someone worse if their body can adapt to use fat as efficiently? There could actually be a few reasons. See when you decrease Carbohydrates for a while, you’re muscle decreases its production of an enzyme called pyruvate dehydrogenase, which helps utilize Carbohydrates as energy (Putman et al., 1993). Basically, as the body becomes more effective at using fat, it becomes less effective at using carbs, which presents a potential problem for high burst activities like a sprint in cycling/running or Sports like Boxing and football where both explosive movements and continuous activity are needed. This probably explains why another study showed a decrease in muscular power and high intensity work with a low carb diet (Fleming et al., 2003). So that’s answering whether the Keto Diet helps Power.

Another reason could be lying in our genes. Research has recently come out showing that variations in the AMY1 gene can affect how quickly and effectively we break down Carbohydrates and how satiated (“full”) we feel after eating them and could even affect how well we perform when eating them or reducing them (Santos et al., 2012).

And strength? Well, research thus far has shown there to be either no difference (Symons et Jacobs, 1989) or a slight improvement in the low carb groups, with a slight improvement in trained individuals when it comes to 1RM measurements (McCleary et al., 2014). I’ll elaborate below.

But what about cosmetic reasons. Does it help weight loss? Improve body composition?

On hell yeah, it does! Not joking either. Nearly all studies show good results when measuring weight loss. And another article on trained individuals actually found an advantage for Muscle gain in the Ketogenic group (McCleary et al., 2014). Success, right? Well, kinda.

See, I’ve never disputed the essential nature of fat in the diet, but going all out and eliminating carbs, in my opinion, is flat out ridiculous. “But what about the studies you just mentioned?!”. The biggest problem I have with all high fat diets is one of two things:

- They don’t control for protein (i.e. the high fat diet was higher in protein than the high carb diet)

- They didn’t control for Omega 3 Fatty Acids (which, again, are far higher in a high fat diet), which have been shown in numerous studies to improve strength and Body Composition, even when taken as part of a high carb diet (Smith et al., 2011; Jouris et al., 2011; Rodacki et al., 2014).

So, what happens when you do control for these factors?

Alright, well, in terms of weight loss, Noakes and colleague’s did a 2006 study that Controlled for total calorie intake, saturated and unsaturated fats Intake and Carbohydrate Intake (these boys are my heroes!) And what did they find?

- Weight Loss – No difference between groups

- Muscle Loss – 31-32% for the high carb AND low carb diets but only 21% loss for the high unsaturated fats group (which was actually a high carb and high unsaturated fats group; check their diets in the study)

- Increase in LDL cholesterol (the bad cholesterol) in the low carb group relative to the others. But in fairness there was also an increase in the HDL (good kind) of cholesterol as well.

And when protein is equated between groups? No significant difference in hunger (Veldhorst et al., 2010), and muscle?

Looks like Noakes is gonna weigh in again, this time with Luscombe-Marsh and colleague’s, with a study showing that not only was there no difference in fat loss between high protein and high fat diet but the high protein group had less hunger overall (Luscombe-Marsh et al., 2005).

However, due to the fact that fat helps decrease water retention (Malik et Hu, 2007) and can be used in a pre-competition or photo shoot protocol to temporarily increase the “shredded” look, there is a HSE for this protocol for bodybuilders/fitness models. But, other than that, looks like whether you’re on a low carb or high carb diet, omega 3/unsaturated fats and high protein help strength and Body composition.

Liquid Diets

I’m doing this next just to get it out of the way! As I’m pretty sure anyone who has half a scientific or intelligent brain is gonna see the obvious practical problems of a HUGE lack of fiber and an associated negative effect on the gut and its healthy bacteria (Alverdy et al., 2014). Not to mention the problem with hunger, even when having the same calories and nutrients as its solid food counterparts (Tieken et al., 2007).

“But what about the juice diets?!” read the above paragraph. We’re built to eat food! So eat food! Stop listening to the Kardashians and go have an apple or something!

So, nothing good on this topic…moving on!

Intermittent Fasting

Alright, now we’re getting interesting. This is probably the newest craze to hit the scene. Intermittent fasting, like low carb diets, comes in a variety of shapes and sizes;

- Lean Gains Intermittent Fasting – Fast for 16 hours, eat for 8. When eating, carry out a training session before you’r due to start your 8 hour feeding period and supplement this session with BCAA’s. Then eat your biggest meal after your session to kick off your 8 hours and eat until your daily calorie and nutrient quota is hit.

- Alternate Day Fasting – Basically, eat whatever you want one day, fast the next. Rinse. Repeat.

- 24hr Fast – Exactly what it says on the tin! One 24hr fast every week!

- 5:2 Fast – 2 Days fasting (they don’t have to be consecutive, any two days will do) and 5 days eating normally

- The Warrior Diet – Eat all your daily calories and nutrients in a four hour window each day.

Alright now here’s where we have a problem. You know how they say no news is good news. Well, that’s not really true for fitness. Thing is, for a method of dieting and eating that’s currently being screamed about on the internet, there not really much research on the specific methods themselves (except alternate day fasting, and even that’s pretty sparse). The closes we have is the studies done on alternate day fasting (ADF) and Ramadan studies. In fact, the best reviews and research in this area can be found in Dr. John Berardi’s Intermittent Fasting case study, which is available at his website of precisionnutrition.com, and Alan Aragon’s review, “An Objective Look at Intermittent Fasting” at his site alanaragon.com.

However, aside from the Lean Gains method, no other fasting protocol really has “rules” on how/what to eat. So, with the lack of specific data, let’s look at what little data we do have and breakdown the elements of Intermittent Fasting to see if we can gather any conclusive data on the separate elements that might help crossover conclusions about the protocols themselves.

Intermittent Fasting (IF) is really just the culmination of two nutritional strategies:

- Nutrient Timing – timing nutrients like protein, carbohydrates, etc. so they’re effect is optimized in the body. This is the same principle that the recommendation to take a protein shake straight after training came from.

- Meal Frequency and size – remember this?! The whole “6 small meals a day for weight loss” craze? That was a fun time.

So what does the research say? Quite a bit actually. While IF hasn’t really been studied in it’s entirety. It’s components have actually researched to near exhaustion.

Existing Data

At the moment Alternate day fasting stands the same as low carb or IIFYM (which is next) protocols. In that it works, but not really any better than normal calorie restriction (Mengmeng et al., 2014) and while there seems to be a fairly high adherence rate in obese subjects (Varady et al., 2009) hunger seems to be elevated throughout the protocol in non-obese health subjects (Heilbronn et al., 2005). Contrary to some beliefs that the fasting is easier on adherence as there has been a disappearance in hunger with fasting or very low calorie diets (Lapalainnen et al., 1995). But this disappearance of hunger observed could be a reason a lot of people find it easier to use IF over normal calorie restriction. But, the strangest thing yet is that IF doesn’t see to impart it’s benefits to women. In fact, ADF has been shown to have a negative effect on glucose tolerance in women (Heilbronn et al., 2005). This actually ties into a talk Berardi gave at an NSCA conference on IF. He himself said how women don’t seem to reap the benefits as much as men, perhaps due to their higher slow twitch fiber type (they have more endurance type muscle than men) when physically active (Martel et al., 2006).

And with Ramadan studies, which closely replicate the 16 hour fast of the Lean Gains method, there seems to be a similar conclusion, albeit with less hunger issues, but with the added detriment of a decrease in speed and agility performance (Zerguini et al., 2007). Also, a complaint noted by Aragon and shared here, is that none of these studies had a control group that followed a normal calorie restricted diet, so its impossible to compare results.

Nutrient Timing Data

So let’s start looking at the components of the protocols. The timing elements of the Warrior Diet and the Lean Gains diet are obvious. The idea is to have your body utilize fat for energy during the fast and then use the Insulin burst from the sudden feed after the workout, along with the increased sensitivity of the muscle after the workout to maximise protein intake and, hence, muscle growth. But does it work?

In terms of muscle growth, a meta analysis by Brad Schoenfeld, Alan Aragon and James Krieger in 2015 showed that, when protein is equal among the experiment and control group, there was a small-moderate effect on Muscle growth for those who timed their nutrients. So this could explain the physique results.

There is also another theory. One that was brought to my attention by my colleague Menno Henselmans’ article on Circadian Rhythm Protein Timing. You can check out the full article at his site bayesianbodybuilding.com but in it he references one study which showed one group being given either carbohydrates in the morning and protein in the afternoon/evening or vice versa (Jordan et al., 2010). The group fed the protein in the afternoon/evening showed superior muscle protein synthesis. Basically, your Circadian rhthym is your biological clock that determines the cycle of certain hormones, including testosterone. And considering most fasters would utilize their daily feeds later in the day, this could provide a reason to the success of IF.

Meal Frequency

And now we but on to the second element of IF. How often someone eats. Now, research has shown that, when total calories and nutrients are equal, meal frequency doesn’t matter, with some research showing some Lean Body Mass lost (Iwao et al., 1996) and some showing a lower frequency to help Lean Body Mass gains (Stote et al., 2007). So, based on the limjted evidence, one could assume that IF may be beneficial when in calirc maintenance or surplis but not as effective when in deficit.

BUT there is one interesting study worth noting. A recent article showing consuming high amounts of protein in a meal can actually reduce Muscle Protein breakdown (Kim et al., 2016).

So, between meal frequency and nutrient timing we have a POTENTIAL mechanism behind the success that some have had with IF but until proper research is done in the area, Berardi’s case study is the best we have.

“And what about the recent research showing the benefits of fasting in Brain health?”

Yeah, there’s some research there alright (Mattson et al., 2000). But this was based on research done on rodents and there is just as much showing the equal benefits of exercise (Seifert et al., 2010) and normal calorie restriction (Araya et al., 2008) on humans.

So, for now, the jury’s out!

IIFYM: If It Fits Your Macros

Ah yes, the current IIFYM craze. I actually like this “protocol” more so than others for it’s flexibility. If you find you do better on low carb, then cut you’re carbs, you prefer carbs? Keep ’em! Just make sure you stick to your daily calorie limit (which you find by calculating your Resting or Basal Metabolic Rate and adjust it for whether you want to gain, lose or maintain your weight) and get enough protein, vitamins and minerals. It allows for flexibility and unpredictability. And with modern technology you can use apps like MyFitnessPal to record and monitor.

But, even this system is not without its limitations.

As you can see from above, there is some merit, particularly for trained individuals and elite athletes, in certain practices like protein timing and low carb dieting. But IIFYM discredits this and takes a “do what you want, just make the numbers” approach. Which may not give optimum results. Plus, we humans don’t have the greatest consistency track record with monitoring or keeping up with our own diets and activity (Burke et al., 1995).

Recommendations:

So, after smashing through all the protocols, what are my personal recommendations. Let’s break them down by the types of goals you may have:

For Ordinary Joes (or Janes) just trying to get in better shape:

Just increase your vitamins, minerals, omega 3s and protein. You can do this by increasing fish, meat and vegetable intake or by taking a fish oil/omega 3 supplement, multivitamin/multimineral supplement and a protein shake. Get into some weight lifting and the physique will improve. If trying to lose weight a bit quicker, pick your least favorite (and least “healthy”) snack food and cut it out every second day. The more improve ent you want, the more snack foods you’ll need to cut.

For Strength/Power/Aesthetic Athletes trying to increase their 1RMs or Muscle Growth:

So, this can apply to Olympic Lifters, Powerlifters, Bodybuilders or even Sprinters and Jumpers I’d definitely recommend a highER fat intake. For Sprinters, Olympic Lifters and Jumpers I’d say around 40% of the diet being fat intake, with this being reduced slightly when coming up to competition periods due to the repeated bouts of effort required. However, for Bodybuilders and Powerlifters I’d actually recommend increasing the fat intake to about 50% coming up to competition periods, bodybuilders and powerlifters for an increase in steroid hormones and to gradually bring down water retention in the bodybuilders before the pre-competition protocol. Again, I would recommend increasing omega 3s and unsaturated fats for this group (they generally don’t take enough). In terms of protein, I wouldn’t actually worry too much about it, seeing as how trained athletes don’t seem to need as much when in maintenance as untrained populations (Tarnapolsky et al., 1992). I’d also recommend a reduced meal frequency and use of Nutrient Timing.

For Endurance athletes trying to improve work rate:

This includes mixed demand groups like footballers and boxers, who need both explosive capacity and continuous Endurance. For these populations I’d recommend carbohydrate as the dominant food source, but also a slightly higher Fat Intake at around 35-40% total dietary intake for runners while boxers/footballers would probably be better served to keep Fat at 35% and increase protein a bit due to the mixed nature of their sport, not to mention the weight making in Boxing and other combat Sports. For high level combat athletes making weight is recommend Nutrient Timing with whey protein if not cutting weight and leucine or BCAAs if cutting, and a higher meal frequency for combat athletes training more than once per day.

Liked the article? Subscribe on our “Community” page free to receive alerts when new articles are published and get sent cool new Nutrition and exercise resources and tips.

References:

Fleming, J., Sharman, M.J., Avery, N.G., Love, D.M., Gómez, A.L., Scheett, T.P., Kraemer, W.J. and Volek, J.S., 2003. Endurance capacity and high-intensity exercise performance responses to a high-fat diet. International journal of sport nutrition and exercise metabolism, 13, pp.466-478.

Knapton, S. (2014) High-protein diet ‘as bad for health as smoking’. Available at: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/science/science-news/10676877/High-protein-diet-as-bad-for-health-as-smoking.html (Accessed: 25 January 2016)

Cox, D. (2016) High carb or high fat? The running diet debate. Available at: http://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/the-running-blog/2016/jan/19/high-carb-or-high-fat-the-running-diet-debate (Accessed: 25 January 2016)

Phinney, S. D., Bistrian, B. R., Evans, W. J., Gervino, E. and Blackburn, G. L. (1983) ‘The human metabolic response to chronic ketosis without caloric restriction: Preservation of submaximal exercise capability with reduced carbohydrate oxidation’, Metabolism, 32(8), pp. 769–776. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(83)90106-3

Putman, C., Spriet, L., Hultman, E., Lindinger, M., Lands, L., McKelvie, R., Cederblad, G., Jones, N. and Heigenhauser, G. (1993) ‘Pyruvate dehydrogenase activity and acetyl group accumulation during exercise after different diets’, The American journal of physiology., (265),

Santos et al. (2012) Available at: http://www.karger.com/Article/Abstract/339951 (Accessed: 25 January 2016)

Symons and Jacobs (1989) ‘High-intensity exercise performance is not impaired by low intramuscular glycogen’, Medicine and science in sports and exercise, 21(5), pp. 550–557.

McCleary, S., Silva, J. E., Lowery, R. P., Rauch, J., Shields, K. A., Ormes, J. A., Sharp, M. H., Weiner, S. I., Georges,, J. I., Volek, J. S., D’agostino, D. P. and Wilson, J. M. (2014) ‘The effects of ketogenic dieting on skeletal muscle and fat mass’, Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 11(Suppl 1), p. P40. doi: 10.1186/1550-2783-11-s1-p40

Smith, G., Reeds, D. N., Rennie, M. J., Atherton, P., Rankin, D. and Mohammed, S. B. (2011) Dietary omega-3 fatty acid supplementation increases the rate of muscle protein synthesis in older adults: A randomized controlled trial1, 2,3. Available at: http://m.ajcn.nutrition.org/content/93/2/402.short (Accessed: 25 January 2016)

Jouris, K. B., McDaniel, J. L. and Weiss, E. P. (2011) ‘The effect of Omega-3 fatty acid Supplementation on the inflammatory response to eccentric strength exercise’, 10(3),

Rodacki, Félix, A. L., Pequito, D., Coelho, I., Nahhas, C. L., Cláudio, L. and José, M. (2015) THE INFLUENCE OF STRENGHT TRAINING AND FISH OIL SUPPLEMENTATION ON BLOOD PARAMETERS OF ELDERLY WOMEN. Available at: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?pid=S1983-30832015000300413&script=sci_arttext (Accessed: 25 January 2016)

Noakes, M., Clifton, P. M., Forster, P., Keogh, J. B., Mamo, J. C. and James, A. P. (2006) Nutrition & metabolism. Available at: http://nutritionandmetabolism.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1743-7075-3-7 (Accessed: 25 January 2016)

Veldhorst et al. (2010) Available at: http://journals.cambridge.org/action/displayAbstract?fromPage=online&aid=7918254&fileId=s0007114510002060 (Accessed: 25 January 2016)

An objective look at intermittent Fasting – AlanAragon.com – fitness based on science & experience (no date) Available at: http://www.alanaragon.com/an-objective-look-at-intermittent-fasting.html (Accessed: 25 January 2016)

Learn more about intermittent Fasting (no date) Available at: http://www.precisionnutrition.com/intermittent-fasting (Accessed: 25 January 2016)

Luscombe-Marsh, N., Noakes, M., Wittert, G., Keogh, J., Foster, P. and Clifton, P. (2005) ‘Carbohydrate-restricted diets high in either monounsaturated fat or protein are equally effective at promoting fat loss and improving blood lipids’, The American journal of clinical nutrition., 4(81),

Malik, V. and Hu, F. (2006) ‘Popular weight-loss diets: From evidence to practice’, Nature clinical practice. Cardiovascular medicine., 1(4),

Alverdy, J., Aoys, E. and Moss, G. (1990) ‘Effect of commercially available chemically defined liquid diets on the intestinal microflora and bacterial translocation from the gut’, JPEN. Journal of parenteral and enteral nutrition., 1(14),

Tieken, S., Leidy, H., Stull, A., Mattes, R., Schuster, R. and Campbell, W. (2007) ‘Effects of solid versus liquid meal-replacement products of similar energy content on hunger, satiety, and appetite-regulating hormones in older adults’, Hormone and metabolic research = Hormon- und Stoffwechselforschung = Hormones et métabolisme., 5(39),

Mengmeng, L., Zhu, X., Wang, H., Wang, F. and Guan, W. (2014) ‘Roles of caloric restriction, Ketogenic diet and intermittent Fasting during initiation, progression and Metastasis of cancer in animal models: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis’, PLoS ONE, 9(12), p. e115147. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0115147

Varady, K., Bhutani, S., Church, E. and Klempel, M. (2009) ‘Short-term modified alternate-day fasting: A novel dietary strategy for weight loss and cardioprotection in obese adults’, The American journal of clinical nutrition., 5(90),

Lapalainnen, R., Vesa, Scnoder, P., T, H. and PMC, E. (1990) ‘Lappalainen R’, International journal of obesity, 14(8), pp. 679–688.

Heilbronn, L. K., Civitarese, A. E., Bogacka, I., Smith, S. R., Hulver, M. and Ravussin, E. (2005) ‘Glucose tolerance and skeletal muscle gene expression in response to alternate day Fasting’, Obesity Research, 13(3), pp. 574–581. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.61

Heillbronn, L., Smith, S. R., Anton, S. and Martin, C. K. (2005) Alternate-day fasting in nonobese subjects: Effects on body weight, body composition, and energy metabolism1, 2. Available at: http://m.ajcn.nutrition.org/content/81/1/69.short (Accessed: 25 January 2016)

Martel, G. F., Roth, S. M., Ivey, F. M., Lemmer, J. T., Tracy, B. L., Hurlbut, D. E., Metter, E. J., Hurley, B. F. and Rogers, M. A. (2006) ‘Age and sex affect human muscle fibre adaptations to heavy-resistance strength training’, Experimental Physiology, 91(2), pp. 457–464. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2005.032771

Zerguini et al. (2007) Impact of Ramadan on physical performance in professional soccer players. Available at: http://m.bjsm.bmj.com/content/41/6/398.short (Accessed: 25 January 2016)

Jordan, L., Melanson, E., Melby, C., Hickey and Miller, B. (2010) ‘Nitrogen balance in older individuals in energy balance depends on timing of protein intake’, The journals of gerontology. Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences., 10(65),

Aragon, A. A., Krieger, J. W. and Schoenfeld, B. J. (2013) The effect of protein timing on muscle strength and hypertrophy: A meta-analysis. Available at: http://www.jissn.com/content/10/1/53 (Accessed: 25 January 2016)

Araya, A. V., Orellana, X. and Espinoza, J. (2008) ‘Evaluation of the effect of caloric restriction on serum BDNF in overweight and obese subjects: Preliminary evidences’, Endocrine, 33(3), pp. 300–304. doi: 10.1007/s12020-008-9090-x

Burke et al. (1995) Adherence to medication, diet, and activity recommendations:…: Journal of cardiovascular nursing. Available at: http://journals.lww.com/jcnjournal/Abstract/1995/01000/Adherence_to_medication,_diet,_and_activity.7.aspx (Accessed: 25 January 2016)

Iwao, S., Mori, K. and Sato, Y. (2008) ‘Effects of meal frequency on body composition during weight control in boxers’, Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 6(5), pp. 265–272. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.1996.tb00469.x

Stote, K. S., Rumpler, W. V., Harris, K. G., Ferrucci, L., Strycula, P., Najjar, S. S., Spears, K., Longo, D. L., Baer, D. J., Ingram, D. and Paul, D. R. (2007) A controlled trial of reduced meal frequency without caloric restriction in healthy, normal-weight, middle-aged adults1, 2,3. Available at: http://m.ajcn.nutrition.org/content/85/4/981.short (Accessed: 25 January 2016)

Kim , 2, A. S., 1, A. F. A., 1, S. S., 1, I.-Y. K. and 2, H. S. J. (2016) The anabolic response to a meal containing different amounts of protein is not limited by the maximal stimulation of protein synthesis in healthy young adults. Available at: http://m.ajpendo.physiology.org/content/310/1/E73.abstract (Accessed: 25 January 2016)

Mattson, M. P. and Wan, R. (2005) ‘Beneficial effects of intermittent fasting and caloric restriction on the cardiovascular and cerebrovascular systems’, The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry, 16(3), pp. 129–137. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2004.12.007

Seifert, 2, P. N., 3, A. J. H., 1, P. R., 3, H. A., 1, M. W., 1, H. N. B. and 1, T. S. (2010) Endurance training enhances BDNF release from the human brain. Available at: http://m.ajpregu.physiology.org/content/298/2/R372.short (Accessed: 25 January 2016)