Menstrual Cycle: Impact On Exercise And Nutrition

The menstrual cycle plays a key role in a woman’s life, having a substantial effect on how a woman exercises and eats, plus how much weight she loses, or strength she gains. In the article below, I take a look at exercise, diet and how to optimise them in each cycle.

Important note: This is a revised edition of the article I wrote for steadyhealth.com (found at: https://www.steadyhealth.com/articles/menstrual-cycle-impact-on-exercise-and-nutrition) , due to some errors seen in the version that was published on the site.

Hormones and the Menstrual Cycle: Nuts and bolts

Ask any healthcare professional, from doctor, to trainer, to exercise physiologist, and they can usually all agree on one thing; Women are complicated. From a medical standpoint, it’s, quite frankly, astounding.

Their immune systems are usually more resilient and they generally recover faster than men from exercise. In terms of nutrition or program design, or even psychology and behaviour, men seem to respond and adapt fairly uniformly to exercise or certain nutrients, such as fat or carbohydrates. This is not always the case for women.

In terms of the current science on exercise and nutrition, we’ve seen a number of gender differences in the response of muscle to strength training. This is also true of the amount of fat that the body can store, and how it stores it.

But what causes these changes?

In one word, hormones. By and large, it’s these hormones, which basically act as chemical messengers to the body, which help control how we respond to exercise and how we eat, but also how we think, how we look, how we act, and pretty much everything about us. Luckily, these hormones can usually be studied and we can begin to understand how our bodies respond to different types of exercise and different foods.

With that in mind, exercise and nutrition in women should be fairly simple to understand then. If women release different hormones to men, all we have to do is understand these hormones and their effects. We can then structure our training programs and diet plans around them, right?

This is where the menstrual cycle comes into play.

See, in men, the hormones that are important for exercise and nutrition, i.e. those influencing fat loss, hunger, muscle growth, strength, etc., remain relatively constant. Their response to different types of exercise and food, such as fats, proteins and carbohydrates, remain fairly consistent too.

But, this is not the case for women. The menstrual cycle causes certain hormone levels to shift and change. This not only makes understanding and studying them more difficult, but structuring exercise and diet programs more difficult too. This could be why women seem to have less long-term success with weight loss than men, or why women seem to suffer more injuries in some joints than men, and seem to suffer more of them during the middle of their menstrual cycle than at other times during the month.

This brings us to the question of what the menstrual cycle is and how someone could adapt their training and nutritional practices to maximize progress.

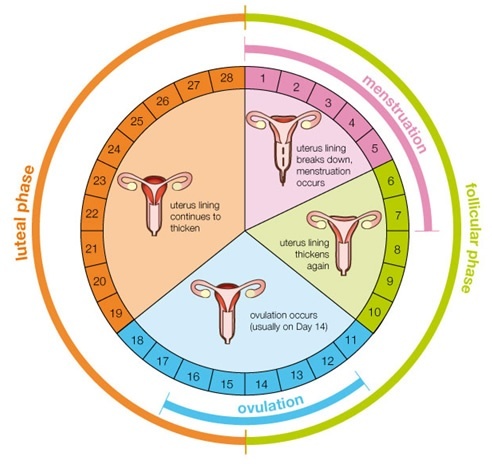

For female readers, the menstrual cycle needs no explanation, but for the more inexperienced male readers, the menstrual cycle is the ‘time of the month’ that’s often mentioned, and the time surrounding it. It’s roughly 4 weeks period (no pun intended), where a woman’s ovaries produce (follicular phase), prepare and release (ovulation phase) and, if not needed, breakdown and excrete (luteal phase) the eggs that would be used for childbirth.

But how could this affect exercise or the way someone’s body uses nutrients?

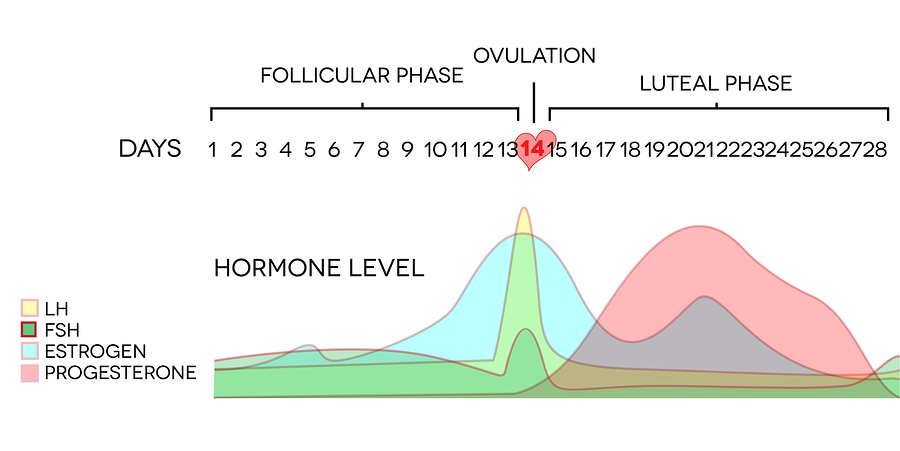

Because, as hinted at above, hormones can play a key role in how hard we can exercise, how well we recover, how much fat we store and how hungry we feel. During each menstrual cycle phase, a woman’s hormones can change pretty drastically.

So, where men might benefit from a relatively consistent exercise and nutritional program throughout the entire month, a woman’s will require a bit more careful planning. With that in mind, we arrive to the exercise and nutrition side of the article.

Exercising And Eating During The Menstrual Cycle

The menstrual cycle plays a key role in a woman’s life, having a substantial effect on how a woman exercises and eats, plus how much weight she loses, or strength she gains.

As was said above, women’s hormones go through quite a change from week to week. This can have some significant effects on the body. For one, during the last two weeks of the menstrual cycle, known as the luteal phase, where the body prepares to excrete an unfertilized egg, the body actually tends to store more muscle glycogen than in the beginning or middle of the menstrual cycle. This may be why many women sometimes complain of bloating in the last two weeks of their cycle.

This has very significant effects on exercise and nutrition as not only can this ‘bloated’ feeling reduce the intensity at which athletes can work, but also because it means that a greater amount of carbohydrates that are consumed by a person during this phase can be converted to fat.

This could indicate that women may be better served to decrease their carbohydrate intake rather than their fat intake during the final weeks of their cycle if their goal is to maximize fat loss on a diet. A practice which has been shown to be more effective than conventional dieting in a recent study.

Another large difference can be seen in the increased recovery capacity women experience during the first two weeks, or the follicular phase, of their menstrual cycle when undertaking exercise. This, again, could be due to higher levels of certain hormones, such as estrogen, which is a group of hormones that causes cells to preferentially breakdown fats over carbohydrate for fuel, and, hence, could improve aerobic, long distance performance at the expense of high intensity exercise. It also helps reduce muscle protein breakdown, and aid recovery from such exercise.

However, muscle protein breakdown and excretion seems to increase during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle. Glucose metabolism also increases as fat metabolism decreases. This is due to dropping and a rise in progesterone.

So, while recovery from exercise may be improved during the initial phase of the menstrual cycle, this may not be an ideal time to increase strength training, as muscle protein synthesis will be negatively affected throughout this period. This, consequently, could also be a good time to increase protein intake.

Putting it into practice

So, now that we have a pretty good concept of how the menstrual cycle can affect hormone levels in women, and how this can then impact someone’s response to exercise or how they use or store different types of nutrients, we can make some recommendations to help minimize some of the negative effects of the menstrual cycle during certain exercises, i.e. increased muscle protein breakdown during certain phases.

We can also use the above information to help maximize the benefits of the menstrual cycle, i.e. improved recovery capacity and fat utilization. With that in mind, here are a few science based recommendations to help maximize exercise performance, improve weight and fat loss, and help improve recovery from exercise:

- If combining strength training and cardio, keep most strength training to the first two weeks of the cycle to maximize strength and lean muscle development.

- During the first two weeks, keep the intensity of any cardiovascular exercise low and steady in nature, i.e. 30 minutes of cycling at a steady pace, rather than interval training or high intensity, which would be better served during the last two weeks.

- Start tapering the volume of any explosive training down after day 10 and be cautious of injury during the middle week of the cycle, and start tapering intensity up by day 18.

- During the first two weeks of the cycle, reduce carbohydrate intake around 10% while keeping protein intake stable and increasing fat intake ~10%. During the last two weeks, reduce fat intake by 20% the same amount while raising carbohydrate and protein intake by~10%

- Also, if completing strength training, a higher volume (up to 5 days of training per week) may be well tolerated during the first two weeks of the cycle, provided that volume is then reduced in the last two weeks (to around one session per week).

References

1. Blaak, E. (2001). Gender differences in fat metabolism. Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition & Metabolic Care, 4(6), 499-502.

2. Fulco, C. S., Rock, P. B., Muza, S. R., Lammi, E., Cymerman, A., Butterfield, G., … & Lewis, S. F. (1999). Slower fatigue and faster recovery of the adductor pollicis muscle in women matched for strength with men. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica, 167(3), 233-240.

3. Galliven, E. A., Singh, A., Michelson, D., Bina, S., Gold, P. W., & Deuster, P. A. (1997). Hormonal and metabolic responses to exercise across time of day and menstrual cycle phase. Journal of Applied Physiology, 83(6), 1822-1831.

4. Lamont, L. S., Lemon, P. W., & Bruot, B. C. (1987). Menstrual cycle and exercise effects on protein catabolism. Medicine and science in sports and exercise, 19(2), 106-110.

5. McCracken, M., Ainsworth, B., & Hackney, A. C. (1994). Effects of the menstrual cycle phase on the blood lactate responses to exercise. European journal of applied physiology and occupational physiology, 69(2), 174-175.

6. Ortner, D. J. (1998). Male-female immune reactivity and its implications for interpreting evidence in human skeletal paleopathology. Sex and gender in paleopathological perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p, 79-92. 7. Riley III, J. L., Robinson, M. E., Wise, E. A., & Price, D. (1999). A meta-analytic review of pain perception across the menstrual cycle. Pain, 81(3), 225-235.

8. Wojtys, E. M., Huston, L. J., Lindenfeld, T. N., Hewett, T. E., & Greenfield, M. L. V. (1998). Association between the menstrual cycle and anterior cruciate ligament injuries in female athletes. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 26(5), 614-619.

9. Geiker, N. R., Ritz, C., Pedersen, S. D., Larsen, T. M., Hill, J. O., & Astrup, A. (2016). A weight-loss program adapted to the menstrual cycle increases weight loss in healthy, overweight, premenopausal women: a 6-mo randomized controlled trial. The American journal of clinical nutrition, ajcn126565.

10. Wikström-Frisén, Lisbeth, Carl Johan Boraxbekk, and Karin Henriksson-Larsén. “Effects on power, strength and lean body mass of menstrual/oral contraceptive cycle based resistance training.” Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness 57, no. 1-2 (2017): 43-52.